There are several Archimedean solids that are formed by the truncation (cutting off) of each corner of a Platonic solid.

These can be shown in successive truncations from one shape to its dual.

| Original | Truncation | Rectification | Bitruncation | Birectification (dual) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Tetrahedron |

Truncated Tetrahedron |

Tetratetrahedron aka Octahedron |

Truncated Tetrahedron |

Tetrahedron |

Cube |

Truncated Cube |

Cuboctahedron |

Truncated Octahedron |

Octahedron |

Dodecahedron |

Truncated Dodecahedron |

Icosidodecahedron |

Truncated Icosahedron |

Icosahedron |

Above images from Wikipedia.com |

||||

Initial truncations remove a pyramid from each corner the original object, the base of which is a regular polygon. If the original face is a triangle, the resultant edges will be \(\frac13\) the original edge; if square, \(\sqrt\frac12\); and if a pentagon, \(\sqrt\frac15\).

Note: Each truncation makes the object smaller, but for the math below, the presumption is an object with edge length of 1.

Complete truncation (also called “rectified”) completely removes original edges, new faces meet a the midpoint of original edges.

Note that the left objects are “sitting” on a face, and the right objects are “standing” on a vertex. This is the result of matching the vertices of one to the midpoints of the dual.

In quasi-regular polyhedra, truncation is not necessarily resultant in regular faces. Adjustments are made to make the faces become regular, these are called rhombi-truncations.

The dihedral angles of the “main” faces (red/red or yellow/yellow) of the truncated object are the same as the original object’s dihedral angles. If there are only three faces at a vertex, the vertex angles are easily found with the formula: \(\Large{\cos\theta=\frac{\cos\epsilon}{\cos(\frac{\mu}{2})}}\), where θ is the vertex angle of the newly created face to the opposing edge, ε is the interior angle of the new main face, and μ is the interior angle of the newly created face.

The dihedral angles of the new faces are a bit harder. We have to do each separately.

Since each truncation removes a pyramid with a regular base, we can calculate the dihedral angle of one side to the base, giving us the complimentary angle to that of the dihedral angle of the new/main faces of the polyhedra. Remember that if A+B=180, then cos A = —cos B, so we can find the cosine of the pyramid’s dihedral angle, then negate it.

Let’s start with the simplest, the truncation of a tetrahedron.

I’ve already done the math for the tetrahedron, the cosine of the dihedral is \(\frac13\), or \(70.528779\ldots^\circ\), so the dihedral cosine for the hexagon-triangle faces of the truncated tetrahedron would be \(-\frac13\), or \(109.47122\ldots^\circ\). The two do add up to 180° and the latter is the same as the rectified tetrahedron (aka octahedron), therefore we are on the right track.

For the trunc. cube, a triangular based pyramid with right angles at the apex, would have a base dihedral of \(cos^{-1}(\frac{1}{\sqrt3})\), so the octagon-triangle dihedral would be \(cos^{-1}(\frac{-1}{\sqrt3})\), or 125.2643897…°.

The trunc. octahedron has a square pyramid (Johnson solid J1) removed that equates to a half octahedron. The dihedral for J1 is \(\cos^{-1}(\frac{1}{\sqrt3})\), so the trunc. octahedron hex-square dihedral would be \(\cos^{-1}(\frac{-1}{\sqrt3})\), or 125.2643897…°.

Yes, these are the same two angles, which can be seen in the cuboctahedron, all edges are square-triangles, so must be the same. It is also evident when you realize that corresponding faces are parallel from one shape to the next during truncation.

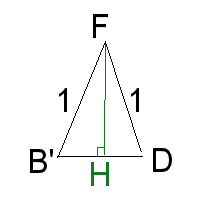

For a trunc. dodecahedron, the decagon-decagon faces have the same dihedral as the dodecahedron. The decagon-triangle edges have the same dihedral as the pent-hex edges of the trunc. icosahedron, 142.622632…°, but we will check this later below.

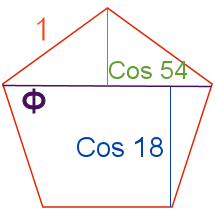

The vertex angle θ is found by

$$\begin{align}\cos\theta &=\frac{\cos108}{\cos\frac{108}{2}}=\frac{-\cos72}{\cos54}

\\&=-\frac{\frac{\sqrt5-1}{4}}{\sqrt{\frac{5-\sqrt5}{8}}}

\\&=-\frac{\sqrt5-1}{4}\cdot\sqrt{\frac{8}{5-\sqrt5}}

\\&=-\frac{\sqrt8 \cdot (\sqrt5-1)}{4\sqrt{5-\sqrt5}}

\\&=-\frac{\sqrt8 \cdot \sqrt{(\sqrt5-1)^2}}{4\sqrt{5-\sqrt5}}

\\&=-\frac{\sqrt8 \cdot \sqrt{6-2\sqrt5} }{4\sqrt{5-\sqrt5}}

\\&=-\frac{\sqrt8 \cdot \sqrt2\cdot\sqrt{3-\sqrt5} }{4\sqrt{5-\sqrt5}}

\\&=-\frac{\sqrt{16} \cdot\sqrt{3-\sqrt5} }{4\sqrt{5-\sqrt5}}

\\&=-\frac{4 \cdot\sqrt{3-\sqrt5} }{4\sqrt{5-\sqrt5}}

\\&=-\frac{\sqrt{3-\sqrt5} }{\sqrt{5-\sqrt5}}

\\&=-\sqrt{\frac{3-\sqrt5 }{5-\sqrt5} }

\\&=-\sqrt{\frac{3-\sqrt5 }{5-\sqrt5} \cdot \frac{5+\sqrt5}{5+\sqrt5} }

\\&=-\sqrt{\frac{10-2\sqrt5 }{20} }

\\&=-\sqrt{\frac{5-\sqrt5 }{10} }

\\

\end{align}$$

So the vertex angle is 121.7174744…°

The trunc. icosahedron we already did the work for, the vertex angles are 148.2825255…°.

We already know the dihedrals of the cuboctahedron and icosidodecahedron are the same as their truncated counterparts, but what if we wanted to verify that?

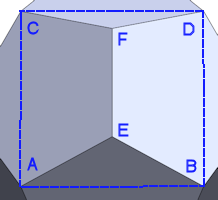

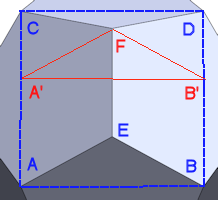

Figure 1: Icosidodecahedron vertex |

As Fig. 1 shows, we can draw a rectangle onto the surface of a icosidodecahedron, with points ABCD, which creates a pyramid with apex E. As lines AD and BC cross the width of the pentagons, their length is then \(Phi\ (\phi)\ or\ \frac{1+\sqrt5}{2}\). The green line is also Φ and crosses AD at point F. Point G is the midpoint of line DE, making DG=EG=1/2.

Notice that the blue and green lines are parallel to the upper and left sides of the pentagon, making a parallelogram, making AF=1, so \(DF=\phi-1 = \frac{\sqrt5-1}{2}\). ∠DGF is 90°, we can find FG,

$$\begin{align}DG^2+FG^2 &=DF^2

\\FG^2&=DF^2-DG^2

\\&=\left(\frac{\sqrt5-1}{2}\right)^2-\frac1{2^2}

\\&=\frac{6-2\sqrt5}{4} – \frac14

\\&=\frac{5-2\sqrt5}{4}

\\FG&=\frac{\sqrt{5-2\sqrt5}} {2}

\end{align}$$

The distance between F and C is

$$\begin{align}CF^2&=CD^2+DF^2

\\&=1+(\frac{\sqrt5-1}{2})^2

\\&=\frac44 + \frac{6-2\sqrt5}{4}

\\&=\frac{10-2\sqrt5}{4}

\\CF&=\frac{\sqrt{10-2\sqrt5}} {2}

\end{align}$$

Line CG is the same as the height of the triangle, \(\frac{\sqrt3}{2}\). Now we can find the dihedral (∠FGC)

$$\begin{align}\cos\angle FGC&=\frac{FG^2+CG^2-CF^2}{2\cdot FG\cdot CG}

\\&=\frac{ \frac{5-2\sqrt5}{4}+\frac34-\frac{10-2\sqrt5}{4}} {2\cdot\frac{\sqrt{5-2\sqrt5}} {2}\cdot\frac{\sqrt3}{2}}

\\&=\frac{ \frac{5-2\sqrt5+3-10+2\sqrt5}{4}} {(\sqrt{5-2\sqrt5})\cdot\frac{\sqrt3}{2}}

\\&=\frac{-\frac24}{\sqrt{5-2\sqrt5}\cdot\frac{\sqrt3}{2}} = -\frac24\div \left(\frac{\sqrt3\sqrt{5-2\sqrt5}} {2}\right)

\\&=-\frac12 \cdot \left(\frac{2}{\sqrt3\sqrt{5-2\sqrt5}}\right)

\\&=\frac{-1}{\sqrt3 \sqrt{5-2\sqrt5}}

\\&=\frac{-1}{\sqrt3 \sqrt{5-2\sqrt5}}\cdot \frac{\sqrt{5+2\sqrt5}}{\sqrt{5+2\sqrt5}}

\\&=\frac{-\sqrt{5+2\sqrt5}}{\sqrt3 \sqrt{25-4\sqrt5-20-4\sqrt5}}

\\&=\frac{-\sqrt{5+2\sqrt5}}{\sqrt3 \sqrt5}

\\&=-\sqrt{\frac{5+2\sqrt5}{15} }

\\\angle FGC&=142.62263\ldots^\circ

\end{align}$$

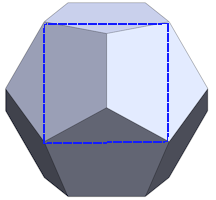

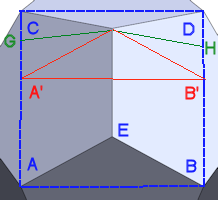

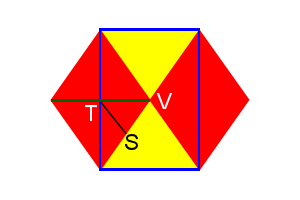

Figure 2: Cuboctahedron vertex |

Just like the icosidodecahedron, we can draw a rectangle onto the surface of a cuboctahedron (Fig. 2), with points WXYZ, which creates a pyramid with apex V. As lines WZ and XY cross the diagonals of the squares, their length is then \(\sqrt2\). The green line is also \(\sqrt2\) and crosses WZ at point T. Point S is the midpoint of line WV, making WS=VS=1/2.

Line ST is half the width of the square, so its length is ½. Lines TV and TW are \(\frac{\sqrt2}{2}\ or \frac1{\sqrt2}\).

The distance between T and X is

$$\begin{align}TX^2&=WX^2+TW^2

\\&=1+(\frac1{\sqrt2})^2

\\&=\frac22 + \frac12

\\&=\frac32

\\TX&=\sqrt{\frac32}

\end{align}$$

Line SX is the same as the height of the triangle, \(\frac{\sqrt3}{2}\). Now we can find the dihedral (∠TSX)

$$\begin{align}\cos\angle TSX&=\frac{ST^2+SX^2-TX^2}{2\cdot ST\cdot SX}=\frac{ \left(\frac12\right)^2+\left(\frac{\sqrt3}{2}\right)^2-\left(\sqrt\frac32\right)^2} {2\cdot\frac12\cdot\frac{\sqrt3}{2}}

\\&=\frac{\frac14+\frac34-\frac64} {\frac{\sqrt3}{2}}

\\&=\frac{-\frac24} {\frac{\sqrt3}{2}} = -\frac24 \cdot \frac2{\sqrt3}

\\&=\frac{-1}{\sqrt3}

\\\angle TSX&=125.2643897\ldots^\circ

\end{align}$$